In a season that was already buzzing with activity, Hurricane Emily stood out early. Having become the earliest Atlantic hurricane on record to reach Category 5 strength, Emily made landfall twice, in the Caribbean and on Mexico’s Gulf Coast. It also showed clear radar and satellite signs like sharp eyewalls and intense convection bursts. More than just powerful, Emily became a standout case study in how fast storms can evolve across the Atlantic.

Formation and Early Development: July 10–13, 2005

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

July 10

A tropical wave exits the west coast of Africa, showing increased convection near the Cape Verde Islands. Conditions across the Main Development Region (MDR) are favorable: low vertical wind shear, above-average sea surface temperatures, and an active African Easterly Jet.

July 11

The system organizes quickly and is classified as Tropical Depression Five by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) while centered east of the Windward Islands.

July 12

Strengthening continues as banding features improve. At 21:00 UTC, the system is upgraded to Tropical Storm Emily. It becomes the fifth named storm of the season - a notable statistic for early July in the Atlantic.

July 13

Emily intensifies despite passing over a dry air pocket. Radar data from long-range ground stations and microwave satellite imagery show signs of a developing core. A broad central dense overcast (CDO) begins to emerge.

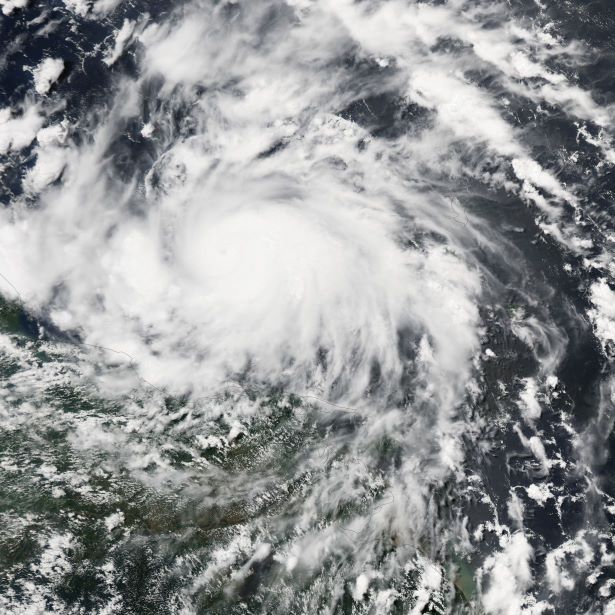

First Rapid Intensification and Caribbean Crossing: July 14–16

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

July 14

Emily enters the Windward Islands and reaches hurricane status near Grenada. Sustained winds are estimated at 75 mph (120 km/h). It becomes the earliest Atlantic hurricane to form east of the Lesser Antilles on record.

July 15

Emily rapidly intensifies over the warm waters of the eastern Caribbean. By evening, it reaches Category 4 strength with winds of 135 mph (215 km/h). An eye becomes clearly visible on both satellite and radar from the ABC Islands.

July 16

Emily peaks at Category 5 intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a central pressure of 929 mb. This makes Emily the earliest Category 5 hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic. Dual eyewalls are briefly detected during the peak, indicating a possible eyewall replacement cycle (ERC) - a process known to modulate storm intensity.

First Landfall: Yucatán Peninsula (July 17–18)

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

July 17

Emily undergoes structural fluctuations and temporarily weakens due to an ERC. By late evening, radar from Cozumel and Cancun shows a well-defined eye approaching the Yucatán coast.

July 18 (06:30 UTC)

Landfall near San Francisco, Quintana Roo, with winds of 135 mph (215 km/h) (Category 4). Emily brings destructive winds and rainfall to Cozumel, Cancun, and Playa del Carmen. Despite weakening slightly before landfall, Emily’s forward speed and small core made real-time radar tracking critical for issuing localized warnings.

July 18 (afternoon)

Emily moves across the Yucatán Peninsula, weakening to Category 1 strength. The low friction terrain slows, but does not destroy, the storm’s core structure.

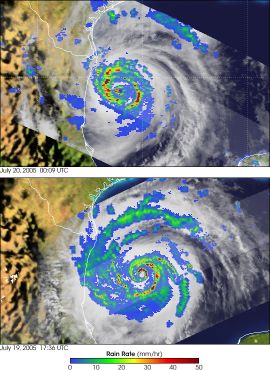

Re-intensification and Second Landfall: July 19–20

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

July 19

Once back over the Gulf of Mexico, Emily reorganizes quickly. The storm takes advantage of exceptionally warm SSTs and modest shear to regain major hurricane status.

July 20 (00:00 UTC)

Emily strengthens to Category 3 with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h). The eyewall becomes circular again, confirmed by Tampico and Brownsville radar as well as recon aircraft.

July 20 (12:00 UTC)

Emily makes its second landfall near San Fernando, Tamaulipas, just south of the U.S.-Mexico border. Torrential rainfall causes widespread flash flooding across northeastern Mexico. Offshore oil platforms report hurricane-force gusts and high waves. Brownsville, Texas, experiences wind gusts near 62 mph (100 km/h) and brief power outages.

July 20-21

Emily weakens quickly over the Sierra Madre Oriental mountains, downgrading to a tropical storm by late July 20 and eventually dissipating on July 21.

Aftermath and Meteorological Legacy

Source: Science Photo Library

Emily caused an estimated $1 billion USD in damages, primarily in Mexico and parts of the southern Caribbean. The storm was directly responsible for at least 17 fatalities. It also broke the following records:

- First Category 5 hurricane ever recorded in July (since reanalysis, later tied with Hurricane Allen in 1980 for July intensity).

- Earliest recorded fifth named storm of any Atlantic season (at that time).

- One of only a few Atlantic hurricanes to make two separate landfalls at Category 3+ intensity.

For meteorologists and storm chasers, Emily offered a textbook example of rapid intensification, eyewall replacement cycles, and post-landfall decay. The ability to track these transitions in near real-time through ground-based radar and satellite-derived radar composites proved vital in refining warnings and understanding hurricane dynamics.

Forecasting Takeaways for Weather Enthusiasts

Hurricane Emily’s evolution offers several important lessons for amateur forecasters and radar observers aiming to sharpen their understanding of tropical cyclone behavior.

Early-season majors are rare, but not impossible

Emily showed that when environmental ingredients align, a tropical storm can reach Category 5 status even in July.

Eyewall Replacement Cycles (ERCs) alter intensity, not necessarily danger

While Emily weakened slightly before landfall, radar imagery showed continued organized structure, indicating high-impact potential despite intensity shifts.

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

Radar and satellite synergy is key

Emily’s evolution was tracked using a mix of long-range radar, aircraft recon, and satellite estimates. Such a trio offers the most complete view of tropical cyclone structure.

Don’t underestimate land interaction

Even brief passages over land like the Yucatán can disrupt core dynamics. However, warm Gulf waters can offer rapid re-strengthening opportunities if the storm survives the crossing.

Final Thoughts

Hurricane Emily (2005) stands as a benchmark for understanding early-season hurricane potential. For the Rain Viewer community, it also serves as a historical case study in the value of radar-based storm tracking. Whether you’re analyzing reflectivity returns, predicting landfall, or studying eyewall structures, Emily offers a rich dataset for amateur forecasters and radar geeks alike.